The Future of Financial Services after Brexit: Options and Limitations

After making sufficient progress on the terms of the UK’s exit from the European Union, negotiations will now move on the thorny issue of forging a future UK-EU trade and investment relationship. The negotiations on the future relationship will resume once the EU leaders adopt guidelines at an EU summit to be held in Brussels during March 22-23, 2018. For the UK, the second phase of Brexit negotiations will be much more difficult than the phase one agreement concluded in December 2017.

As planned, the UK will formally leave the European bloc in March 2019 but will remain in a transition arrangement with the EU for a two-year transition period during which it would stay in the single market and customs union. Given the limited timeline to conclude a substantial new trade deal, the UK’s negotiation position vis-à-vis the EU is weak and, therefore, Brussels may have the upper hand in the second phase of Brexit negotiations.

The UK’s Financial Services Sector

The financial services sector plays a pivotal role in the UK economy. The financial and related professional services accounts for 11.8 percent of UK’s GDP.[1] According to TheCityUk – the lobbying group representing UK-based financial services industry – the UK’s trade surplus in financial services was $77 billion in 2016, more than the combined surpluses of the next two leading countries – the US and Switzerland.[2] The UK’s financial services sector is the biggest source of tax revenue, contributing 11.5 percent of total tax receipts in 2016.[3] Besides, the UK is also a global leader in providing a wide range of professional services – from accounting to legal services. According to official statistics, the UK’s financial sector provided jobs to around 1.1 million people (3.4% of total workforce) in 2016. [4]

London is the world’s leading international financial center in the world followed by New York, Hong Kong, and Singapore. London dominates foreign exchange trading, accounting for 37 percent of global turnover. [5] London’s financial center, “the City,” has more foreign banks than any other city in the world although most foreign banks actually do little business with UK clients.

London is also the financial hub of the EU. Olivier Wyman, a management consulting firm, has estimated that out of £200 billion of annual financial services revenues generated in the UK, as much as £40-50 billion (25 percent) is related to EU client activities.[6]

Several segments of UK and European financial markets are closely intertwined. It has been estimated that more than half of European investment banking activity is conducted in the UK. Big European banks (such as Deutsche Bank, BNP Paribas, and Societe Generale) conduct a significant part of their investment banking activities across the UK.

In 2015, Deutsche Bank, the biggest European bank, generated €6.3 billion (19 percent of its total revenue) from its banking business across the UK where it employs roughly 9000 staff.[7] France’s biggest bank, BNP Paribas, has around 6500 staff based in the UK.

To a large extent, the success enjoyed by the UK is due to the functioning of the EU single market which allows unfettered access to the European markets. A large number of non-EU international banks (such as Goldman Sachs, Bank of America and Credit Suisse) and financial firms use London as an entry point to access European single market. They provide a wide range of services to EU clients via their UK-based subsidiaries.

Table 1 shows the high concentration of EU financial market activity, especially in OTC derivatives and foreign exchange trading, hedge fund activity and marine insurance, in the UK.

Table 1: UK share of Financial Markets in the EU

| % share of UK | Date | |

| Interest rate OTC derivatives trading | 82 | Apr-2016 |

| Foreign exchange trading | 78 | Apr-2016 |

| Hedge fund assets* | 85 | 2014 |

| Private equity funds raised* | 49 | 2014 |

| Marine insurance premiums | 65 | 2014 |

| Fund management | 50 | 2014 |

| Equity market capitalization (LSE) | 30 | 2014 |

| Financial services GDP | 23 | 2014 |

| Bank lending | 26 | 2014 |

| Banks assets* | 21 | 2014 |

| Insurance premiums | 22 | 2014 |

| Financial and professional services employment | 15 | 2014 |

* % share of Europe.

Source: TheCityUK, 2016.

Due to such high concentration of EU financial market activity in the UK, there are concerns of new risks posed by market fragmentation to the entire financial system if there is a no future deal between the UK and the EU after the Brexit.

Therefore, post-Brexit, the issue of market access in financial services is important not only for the UK but also for the EU because European banks and firms currently operating in the UK may face higher costs and potential disruption. Since the economic stakes on both the UK and the EU sides are too high, it is in everyone’s interest to carefully negotiate because financial services require harmonization of countries’ domestic regulations which, in turn, raises sovereignty and policy autonomy concerns. No wonder, negotiations on financial services tend to be technically complex and time-consuming.

Unlike insurance sector which is more globally oriented and therefore less at risk, the rest of financial sector will require delicate negotiations due to the interconnectedness of financial services between the UK and the rest of EU. Needless to say, a lot will depend on mutual trust and cooperation on both sides.

Will London lose its Pre-eminence after Brexit?

Will London remain the financial hub of Europe after Brexit? Can financial services easily be replicated elsewhere in Europe?

Some analysts argue that Frankfurt or Paris or Dublin or Amsterdam could possibly emerge as an alternative financial center within the EU in a post-Brexit scenario. No one can deny the possibilities of such alternative financial centers attracting a sizeable business, especially euro-denominated clearing, away from the UK. However, in the short to medium term, it would be very hard to replicate London given its well-developed financial ecosystem consisting of favorable time-zone; talented workforce; sound legal system; its English language which has become the global business lingua franca; and expertise in a wide range of professional services. Hence, London’s position as the financial center of Europe cannot be easily replicated within the bloc in the near term.

Options for the UK

Broadly speaking, there are four options for the UK’s post-Brexit relationship with the European Union in the area of cross-border trade and investment in financial services.

The first option is a bespoke trade agreement between the UK and the EU that includes a specific chapter on financial services scheduling deeper commitments. Such an agreement would secure access to the single market for the UK-based financial institutions and vice-versa in the UK for the EU-based financial institutions.

The second option for the UK is to become a member of European Economic Area (like Norway) that would enable its firms to continue to provide services to European clients without much regulatory hindrance based on the principle of single ‘passport’ and mutual recognition.

The third option for the UK is to rely on EU’s existing third-country equivalence regimes. Under this option, the UK becomes a third country (like China and India) outside the EU/EEA but its financial firms can still have conditional access to the EU single market depending on specific arrangements to be made under EU financial services legislation.

If none of the above three options came to fruition, trade in financial services between the UK and the EU will take place as per the rules of General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) of the World Trade Organization (WTO).

The UK government has not yet confirmed which particular option it would like to pursue with the EU after leaving the bloc. However, media reports suggest that the UK will prefer a deal somewhere between a Norway-style single market agreement and a free-trade agreement.[8]

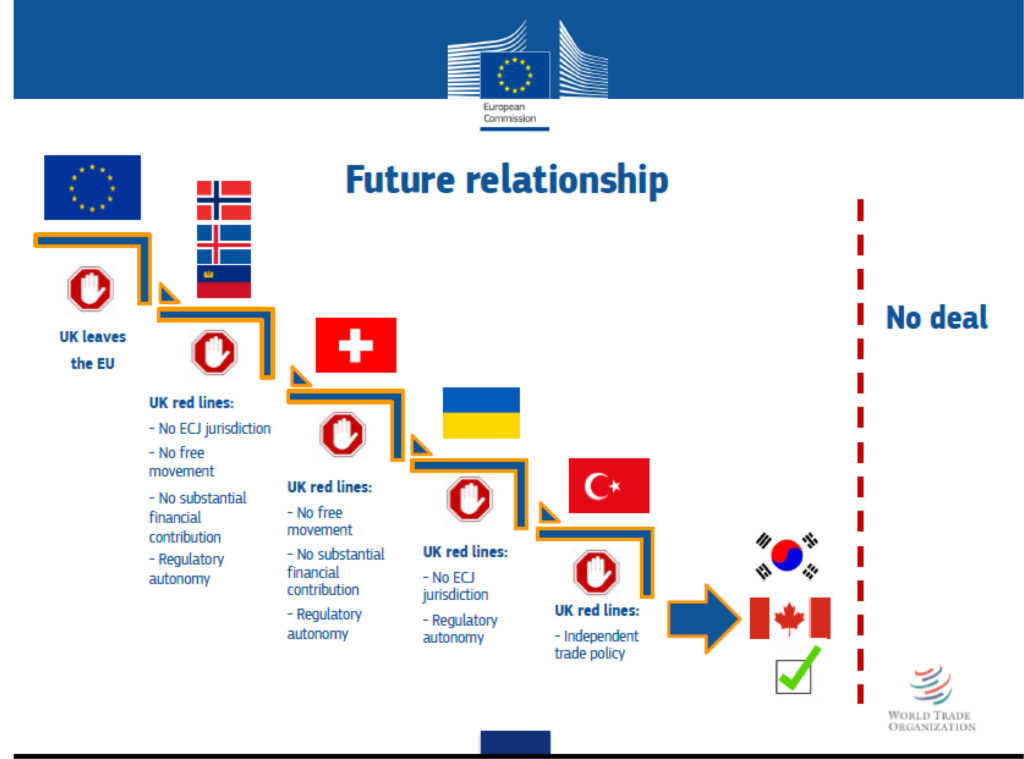

On December 15, 2017, Michel Barnier, the EU’s chief Brexit negotiator, presented a slide to EU leaders in which he has depicted various options for future trade relationship based on the UK’s self-imposed “red lines” to be free of European courts, trade rules, movement of people, and financial contribution.[9] The slide (pasted below) is self-explanatory and therefore needs no further explanation.

Source: Michel Barnier, 2017.

Since the UK’s “red lines” will be the driving force behind negotiations, two options appear most likely: a future agreement similar to EU-Canada trade pact or the default WTO option under which the UK and the EU will trade as per WTO rules in the event of a ‘no-deal’ Brexit scenario.

The UK’s four options for a future relationship with the EU are discussed in details below.

A Bespoke Trade Agreement

British Prime Minister, Theresa May, is keen to pursue to a comprehensive bespoke trade agreement with the EU with a modified customs union deal that would allow the UK to negotiate preferential trade agreements around the world besides a chapter on financial services offering deeper market access commitments close to passporting rights. In particular, the UK government will be keen to replicate the Capital Requirements Directive (CRD IV), which covers wholesale and retail banking services, either under a specific chapter of UK-EU free trade agreement or a customized agreement on financial services. This would protect London’s status as a center of international banking after Brexit.

David Davis, the Brexit secretary, remains confident that the country can negotiate a bespoke deal with the EU and has proposed a “Canada plus plus plus” agreement based on the Canada-EU trade agreement (CETA) with additional market access commitments on financial services.[10] In a meeting with senior executives representing banks and other financial institutions, Theresa May also reiterated her commitment to put financial services at the center of a bespoke deal with the EU.[11]

Theoretically speaking, a bespoke trade agreement between the UK and the EU is feasible. However, currently, there is no FTA (including CETA) that can provide similar levels of market access and passporting rights to the UK-based banks and financial firms that are currently available within the EU single market. CETA contains a chapter on financial services but it does not provide the kind of market access that the UK government is looking for in EU27 member-states. Further, CETA also contains a Most Favoured Nation (MFN) clause which implies that if the EU offers greater market access in financial services to the UK, it will have to offer that improved market access to Canada and all other trading partners with whom it has concluded FTAs with chapters on trade in financial services and investments with MFN clauses.

Therefore, the existence of MFN clauses in its existing free trade agreements with Canada and South Korea will constrain the EU to offer a special favorable deal on financial services to the UK. Michel Barnier has ruled out any possibility of a bespoke trade agreement that would preserve full access to the EU single market in financial services. In an interview with The Guardian, Barnier said that British banks and other financial institutions would lose the privileged access to EU markets (granted under the current EU passporting system) after leaving the single market. “There is no place [for financial services]. There is not a single trade agreement that is open to financial services. It doesn’t exist…In leaving the single market, they lose the financial services passport,” said Barnier. [12]

A similar observation was made recently by French President, Emmanuel Macron, at a UK-France summit when he asked the UK to contribute to the EU budget and accept the jurisdiction of EU courts if it wants special access for its financial services firms to the single market after Brexit. He stated: “I want to make sure that the single market is preserved because that is very much the heart of the EU. The choice is on the British side, not on my side. But there can be no differentiated access for the financial services. If you want access to the single market – including the financial services – be my guest. But it means that you need to contribute to the budget and acknowledge European jurisdiction.”[13]

It is highly unlikely that the UK will accept the jurisdiction of EU courts and will pay into the EU budget in return for full market access in financial services after Brexit. Unless there is a major rethink on self-imposed Brexit “red lines” by the UK government, there is a slim hope for striking an ambitious trade deal with deeper market access commitments on financial services outside of the EU single market.

The EU Financial ‘Passport’

Post-Brexit, the UK can retain full access to the EU single market in financial services based on the ‘passport’ system and the principle of mutual recognition by seeking the membership of the European Economic Area (i.e., the Norwegian option). The ‘passport’ system and the principle of mutual recognition system are at the heart of the EU single market in financial services which give the freedom to provide services and the freedom of establishment to EU-based banks and other financial firms to conduct cross-border business across the bloc on the basis of a single authorisation from the competent authority of the home member-state.

This single authorization mechanism is known as the financial services ‘passport.’ Using this mechanism, for instance, a UK-based financial firm can obtain regulatory authorization (‘outward passport’) from Financial Conduct Authority of the UK and can then provide services directly cross-border (e.g., via internet) or by establishing branches anywhere within the EU without obtaining a separate authorization from other member-states. Likewise, a financial firm from other EU member-states can conduct business in the UK by using an ‘inbound passport’ issued by the regulatory authority of that member-state to that firm.

The EU passporting system offers many advantages. These include special privileges to EU-based firms to provide cross-border financial services across the bloc as passports are not available to firms incorporated outside the EU; less complexity and lower costs in conducting cross-border business; and relatively few additional requirements imposed by host member-states.

However, a single ‘passport’ does not cover all financial services. There are currently nine EU-wide passports covering a wide range of financial services. Banks and financial institutions have to obtain multiple passports for providing different kinds of financial services (such as deposit-taking and credit, insurance, and investment services) as per the EU regulatory framework embedded in different legislative acts such as Capital Requirements Directive (CRD IV), the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID II), and the Markets in Financial Instruments Regulation (MIFIR).

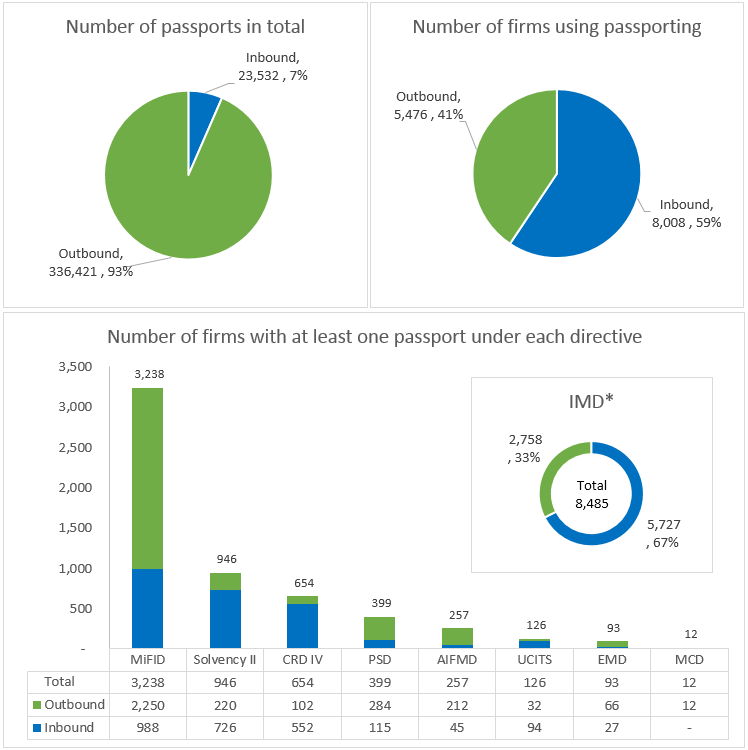

Currently, a large number of firms from the UK and the EEA use financial passports to provide services on a cross-border basis. According to the statistics provided by the Financial Conduct Authority of the UK, 359,953 passports have been issued to 13484 firms, out of which 8,008 financial firms based in 27 member-states of EU are using ‘inbound passports’ to conduct business in the UK whereas 5,476 firms based in the UK are using ‘outbound passports’ to conduct business in other EEA member-states[14] (see Figure 1).

Owing to passporting rights and the principle of mutual recognition, international banks have been using London as a hub and entry point seeking access to the EU’s single market. That’s why a large number of international investment banks are located in London and they use a UK license as ‘outbound passport’ to serve EU’s single market.

Without such rights, the UK-based banks and financial firms will have to meet the entry requirements for setting up subsidiaries or opening up branches in each individual EU member-states thereby incurring additional costs and paperwork. Same will be the case with the EU financial firms seeking access to the UK’s financial services market.

Figure 1: The Issuance and Usage of EU Financial Passports* (FCA, UK)

*As on 27 July 2016.

Source: BrexitFinancial, 2017.

If the UK is unable to secure a future deal guaranteeing full access to the EU single market, its financial firms would be impacted negatively in the short-and medium-term because their business model is based on passporting rights and they generate substantial revenues from their cross-border business operations in the EU27 member-states. In particular, the banking industry would be adversely affected with major impacts on the wholesale banking business rather than on retail or online banking. In the absence of passporting rights, a substantial part of UK’s wholesale banking and trading business may move out to other European jurisdictions. Likewise, financial institutions from the EU would no longer be able to use financial passports while seeking access to Britain’s financial services market.

In contrast, insurance industry may not feel the pinch because it relies less on the ‘passport’ system.

Nevertheless, the moot question is – Will the UK decide to stay in the single market by becoming an EEA member? As anti-immigration sentiment is widespread in the UK, it is highly unlikely that the current government would accept free movement of citizens (including workers) enshrined in EU treaties and made operational through the ‘four freedoms’ of the single market – free movement of goods, capital, services, and people. From the EU’s perspective, however, the ‘four freedoms’ are indivisible.

Furthermore, the UK may not be interested in seeking an EEA-type relationship as it would entail substantial financial payments besides accepting EU’s regulations and its supranational institutions (such as the European Court of Justice) without having a voice at the table. After all, “take back control” was the slogan used by the leave campaign in the run-up to the Brexit referendum. It would be very hard for the UK government to justify acceding even more control to the EU regulations without any say over regulatory changes.

Time and again, Theresa May has stated that her government would take back control over country’s borders and end the supremacy of EU law over the UK. Hence from a political viewpoint, the Norway option seems unviable.

Third-Country Equivalence Regime: A Piecemeal Approach

Once the UK leaves the European bloc, it would be considered as a “third country” under EU law. However, its banks and financial firms can still have conditional access to the EU single market in specific activities if the EU (the European Commission or relevant supervisory bodies) recognizes that the regulatory regime of the UK is “equivalent” to the corresponding EU regime.

Some analysts consider the third-country regimes (TCRs) as a long-term solution for mitigating the effects of the loss of the passporting rights because it removes additional regulatory hurdles for third countries. However, the TCRs are highly problematic for four key reasons.

Firstly, third-country regimes are not comprehensive. They cover a very small proportion of financial services. The equivalence-based market access provisions do not exist for most financial services that are currently covered by the passporting regime and in cases where equivalence provisions exist, they are narrow in scope. For instance, no equivalence-based market access rights exist under the Capital Requirements Directive (CRD IV) for a wide range of banking services such as deposit-taking, lending, broking, securities issuance and portfolio management (see Table 2). The Undertakings for the Collective Investment in Transferrable Securities (UCITS) Directive regime for asset management does not provide equivalence-based market access provisions for the third country.

The Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (AIFMD) – which deals with alternative funds such as hedge funds, private equity, real estate funds and venture capital – also has no equivalence provisions for cross-border market access. Similarly, there are no equivalence provisions in electronic money services.

In certain segments of investment services, equivalence provisions are included in the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID II) and the Markets in Financial Instruments Regulation (MIFIR) but their scope is very narrow. For instance, the scope of market access for third country firms is only limited to wholesale investment products for “per se professional clients” and with market counterparties and only directly cross-border. The Insurance Mediation Directive (IMD) provides a very limited third-country equivalence regime for sale of insurance products across the EU/EEA.

In general, TCRs only provide limited rights of access for serving retail clients. If investment firms from the third country intend to deal with retail clients, they will have to establish a branch in a member-state and must register with the European Securities and Markets Authority besides reciprocal cooperation agreements between ESMA and the regulatory authority of third-country must be in place.

Table 2: EU’s Passporting and Third Country Regimes in Selected Financial Services

| Type of Business | Passport available? | TCR for cross-border access without a branch? |

TCR for branch access? |

| Banking and related services | |||

| Deposit-taking | Yes | No | Yes* |

| Lending (non-consumer) | Yes | No | No |

| Lending (consumer) | Yes | No | No |

| Providing mortgages | Yes | No | No |

| Foreign exchange services | Yes | No | No |

| Payment services | Yes | No | No |

| E-commerce and issuing electronic money | |||

| E-commerce | No | No | No |

| Issuing electronic money | Yes | No | No |

| Investment Services | |||

| Retail investment business (retail client and elective professional clients) |

Yes | No | Yes |

| Wholesale investment business (per se professional clients and eligible counterparties) |

Yes | Yes* | Yes* |

| Funds and fund management | |||

| Acting as a fund (UCITS or ELTIFs) |

Yes | No | No |

| Fund management (UCITS or ELTIFs) |

Yes | No | No |

| Insurance and reinsurance | |||

| Insurance and reinsurance undertakings | Yes | No | Yes* |

| Insurance mediation and distribution | Yes | No | No |

* If authorized by the host state.

Source: Compiled by author.

Therefore, the scope of market access will be very limited for the UK-based firms under the EU’s existing equivalence regimes once the UK becomes the third country.

Secondly, the procedures involved in securing third-country equivalence rights are complex and time-consuming. The EU will make an assessment of a third-country regulatory framework on the basis of three aspects: i) the requirements are legally binding; ii) they are subject to effective supervision by local authorities; iii) they achieve the same results as the EU corresponding rules.

The process involves a rigorous and lengthy assessment of regulatory regime of a third-country besides signing of co-operation agreements between the competent supervisory authorities. There are no timelines for completing assessments. Take the case of the equivalence of the US regulatory framework for central counterparties (CCPs) under European Market Infrastructure Regulation (EMIR). It took up to 4 years for the European Commission to recognize the regulatory framework of the US’s Commodities and Futures Trading Commission for Central Counterparties (CCPs) as equivalent to the corresponding EU regime.

Thirdly, there is no unanimity over what “equivalence” actually means in practice. Unlike the passporting and mutual recognition regimes, the process of declaring a regulatory regime equivalent is highly uncertain as it is often driven by political considerations rather than technical assessments. Thus, aligning a country’s regulatory framework closer to the corresponding EU framework alone is not enough to secure equivalence rights.

Lastly, and perhaps more importantly, the equivalence decision is a purely unilateral and discretionary act by the EU as it can be changed or withdrawn anytime if the EU finds that the third country’s regulatory regime has diverged from its own. The European Commission has the power to withdraw equivalent status at little or no notice. For instance, under MiFID II, ESMA can withdraw registration of a third-country financial firm if it finds, inter alia, that the conduct of that firm could potentially harm the orderly functioning of financial markets. In contrast, the EU’s financial passporting rights are permanent in nature.

In other words, the entire process under the TCRs is controlled by the EU and the third country has no say in the determination or termination of equivalence status. As a result, there is an inherent risk for the third-country financial firms as their market access rights can be unilaterally removed by the EU if two regulatory regimes diverge for any reason. Therefore, it would be erroneous to assume that the third country regimes can provide the same level of stability and market access for financial firms as the passporting and mutual recognition regimes for EU/EEA firms.

Some analysts argue that the UK can easily secure third-country equivalence status post-Brexit as it has fully implemented the EU’s financial services legislation. In theory, yes, but it will take some time to secure equivalence status and a lot would depend on other factors such as mutual trust and cooperation.

Besides, the UK will have to regularly update its regulatory framework if the European Commission decides to introduce new rules or revise existing regulations. One key issue is how long the UK will align its financial regulations given its historical preference for Anglo-Saxon ‘light touch’ regulation of financial markets. Thus, maintaining an equivalence regime in the future will be a challenging task for the UK’s regulatory authorities.

UK: A “rule-taker’ or ‘rule-maker’?

The question of sovereignty was at the heart of the Brexit referendum. However, under the third-country equivalence regimes, the UK will have to keep its regulatory rules sufficiently closely aligned with the EU rules so that its financial firms can serve European clients. In other words, the EU’s demand for increasing regulatory convergence will undermine the UK’s desire for greater regulatory freedom. Will the UK accept the loss in regulatory freedom in order to gain conditional market access under the TCRs?

Moreover, the UK will not have any say when the EU drafts regulations on financial services in the future. Paradoxically, the UK may end up as a pure ‘rule taker’ rather than a ‘rule-maker.’

This issue becomes even more important as the EU is currently re-examining existing equivalence rules with an objective of toughening its criteria for granting equivalence rights to systemically important non-EU financial centers.[15] For the UK, this new move does not bode well as its regulatory regime will have to undergo tougher scrutiny to meet the new requirements for equivalence tests.

A key bone of contention between the two sides will be the capping of bankers’ bonuses. Mark Carney, the governor of the Bank of England, has recently suggested scrapping of EU rules on capping bankers’ bonuses after Brexit.[16] Under the equivalence regime, however, the UK will have to respect the EU rules on bankers’ bonuses. So it remains to be seen whether the UK will sufficiently align its regulatory regime with the EU rules for securing third-country equivalence status.

Goodbye EU, Hello WTO

Under a ‘no deal’ scenario, the UK’s trading relationship with the EU will be governed by the WTO rules. The cross-border trade in financial services will be conducted under the GATS schedules. The UK is a member of WTO – both individually and as a member-state of EU – even though it operates through the European bloc and its status at the WTO is governed by EU’s commitments. After Brexit, the UK will continue to be a member of WTO but it will have to issue UK-specific commitments on financial services (known as schedules) which need to be certified by all member-countries of WTO.

Under the current GATS rules, however, cross-border trade in financial services is limited in scope and therefore would not give the UK-based banks and financial firms the same kind of market access which they currently get under the single market or the EU-South Korea FTA (entered into force 2011).

Undeniably, a ‘no deal’ Brexit would have far-reaching legal and economic implications for UK-based financial firms as they will face new regulatory and prudential barriers in providing cross-border banking and investment services to European clients. In addition, non-EU financial firms may move their European business operations from the UK to a European jurisdiction in order to benefit from the EU’s financial services ‘passport.’ Both these scenarios will result in considerable job losses in the City.

Under a ‘no deal’ scenario, a UK-based financial firm will have to establish a subsidiary in continental Europe and acquire a license from the local regulatory authority in accordance with local laws. In case a UK-based financial firm is already serving European clients through branches under a financial ‘passport’, it will have to either convert those branches into local subsidiaries or cease operations. Same will the case with the EU-based firms wishing to do business in the UK. As subsidiaries are subject to strict capital and liquidity requirements, banks and other financial firms will face additional costs due to higher overhead costs and complexities involved in setting up independent subsidiaries.

Some analysts argue that the UK could compensate the potential loss of EU-related business by pursuing bilateral free trade agreements with Hong Kong, Singapore, India, Australia and the US but it could take years and decades to conclude FTAs with deeper commitments on financial services as desired by the City.

Singapore-on-Thames?

What will the future of financial regulation in the UK after Brexit? Outside the EU, the UK could be freed from EU regulations such as bonus caps, Solvency II standards and the proposed financial transaction tax. However, there will be no bonfire of financial regulations post-Brexit, as fantasied by financial services industry. Post-Brexit, the UK will have to abide by capital requirements rules for banks set by Basel Committee on Bank Supervision and global anti-money laundering standards established by the Financial Action Task Force. The UK would still be bound to follow regulatory standards set by other global standard-setting bodies such as IOSCO, IAIS and OECD. Mark Carney currently chairs the Financial Stability Board (FSB) that monitors and makes recommendations on developing strong regulatory and supervisory financial sector policies. In a post-crisis world, a highly deregulated financial sector is neither feasible nor desirable.

Some see Brexit as an opportunity to turn the UK into the ‘Singapore of Europe’ by slashing corporate taxes. In her Lancaster House speech outlining her Brexit objectives, Theresa May also threatened to change the basis of Britain economic model if the European countries don’t offer a good deal. She stated: “No deal for Britain is better than a bad deal for Britain…We would have the freedom to set the competitive tax rates and embrace the policies that would attract the world’s best companies and biggest investors to Britain. And – if we were excluded from accessing the single market – we would be free to change the basis of Britain’s economic model.”[17] But transforming Britain into a corporate tax haven is not what the people voted to leave the EU as it would lead to the dismantling of vital public services like the NHS which are financed out of tax revenues. Not many British people will yearn to adopt such an economic model.

In the midst of ongoing discussions on the post-Brexit options, an important policy issue related to the rebalancing of the UK’s economy is not getting adequate attention. Needless to say, Brexit offers an opportunity to rebalance the UK’s economy that is too reliant on financial services and on the City rather than on research and development (R&D) based manufacturing elsewhere in the country. Manufacturing accounts for just 10 percent of country’s GDP. On this issue, the ball is entirely in the UK court.

Endnotes

[1] UK Financial Centres of Excellence, UK Trade & Investment, February 2016.

[2] Key Facts about the UK as an International Financial Centre, TheCityUK, December 2017.

[3] Total Tax Contribution of UK Financial Services, City of London Corporation Research Report, December 2016.

[4] Labour market statistics, JOBS05: Workforce jobs by region and industry, Office for National Statistics, October 2016.

[5] Central Bank Survey: Foreign Exchange Turnover in April 2016, Bank of International Settlements, September 2016.

[6] Oliver Wyman, The impact of the UK’s exit from the EU on the UK-based Financial Services Sector, commissioned by TheCityUK, 2016.

[7] Annual Report, Deutsche Bank, 2015; Steven Arons, “Deutsche Bank’s Matherat Says 4,000 UK Jobs at Risk in Brexit,” Bloomberg, April 26, 2017.

[8] See, for instance, George Parker, “Macron boosts May’s hopes of bespoke EU trade deal,” Financial Times, January 20, 2018.

[9] Michel Barnier, European Commission, December 19, 2017. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/slide_presented_by_barnier_at_euco_15-12-2017.pdf.

[10] “Brexit: David Davis wants ‘Canada plus plus plus’ trade deal,” www.bbc.com, December 10, 2017. Available at: http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-42298971.

[11] Martin Arnold and others, “UK promises to prioritise financial services in Brexit deal,” Financial Times, January 12, 2018.

[12] Jennifer Rankin, “UK cannot have a special deal for the City, says EU’s Brexit negotiator,” The Guardian, December 18, 2017.

[13] Quoted in Andrew Sparrow, “What Macron says about UK having reduced trade access to EU if it leaves single market,” blog, www.theguardian.com, January 18, 2018. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/blog/live/2018/jan/18/macron-may-summit-french-president-emmanual-macron-theresa-may-labour-mp-calls-for-windfall-tax-on-pfi-companies-politics-live?page=with:block-5a60ef3ce4b0ff81ba724d58#block-5a60ef3ce4b0ff81ba724d58

[14] Correspondence from Andrew Bailey, Chief Executive of the Financial Conduct Authority, to Andrew Tyrie Chairman of the Treasury Committee, August 17, 2016. Available at: https://www.parliament.uk/documents/commons-committees/treasury/Correspondence/AJB-to-Andrew-Tyrie-Passporting.PDF.

[15] Jim Brunsden, “Brussels signals tough stance on UK bank bonuses after Brexit,” Financial Times, December 19, 2017.

[16] Caroline Binham, “Bankers’ bonus cap could be scrapped after Brexit, says Carney,” Financial Times, November 29, 2017

[17] The full text of Theresa May’s speech is available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/the-governments-negotiating-objectives-for-exiting-the-eu-pm-speech.

Photo courtesy of Flickr

To download this paper in pdf format, click on ‘Download Now’ link given below.