India’s Vaccine Diplomacy: A Potent Tool to Fight COVID-19 in the Global South?

For over two decades, India has acquired the reputation of being the ‘pharmacy of the world’ as its strong generic pharmaceutical industry has supplied affordable medicines to the global markets. Exports of medicines from India, which were around a billion dollars at the turn of the century, had increased to over $20 billion in 2019-20.

Indian companies had made critical interventions during the HIV/AIDS pandemic by supplying affordable antiretroviral medicines to African countries when the major pharmaceutical producers had demanded excessively high prices for these medicines. Subsequently, after the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria took shape as a multi-stakeholder initiative to reduce these diseases’ burden, India’s generic industry emerged as one of the largest suppliers.

In keeping with its historical role, India has now emerged as one of the major suppliers of vaccines to overcome the scourge of the COVID-pandemic. The country can play this role given its partnership with the Serum Institute of India (SII), the world’s largest vaccine manufacturer by the number of doses (the company claims it can produce 1.5 billion doses annually).

In June 2020, SII entered into a licensing agreement with AstraZeneca, a British-Swedish pharmaceutical company, to supply one billion doses of the Oxford University COVID vaccine to middle and low-income countries, including India. SII is currently providing its vaccine, Covishield, to the Government of India. Before this tie-up, another Indian biopharmaceutical company, Bharat Biotech International Ltd, together with the Indian Council of Medical Research, the government agency promoting biomedical research, began their collaboration developing a COVID vaccine, Covaxin.

Even as it was organising its COVID-vaccine roll-out, the Indian government announced an elaborate ‘vaccine diplomacy’ strategy for providing vaccines to most of its neighbours and many other developing countries, including those from Africa. India’s six neighbouring countries (Afganistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Maldives, Nepal, and Sri Lanka) will benefit from the vaccine supplies as part of the government’s development cooperation initiative.

Other countries that have already received ‘vaccine assistance’ are Seychelles, Myanmar, and Mauritius. In the South Asian region, in which China’s growing presence has been discernible over the past few years, the Government of India’s ‘vaccine diplomacy’ could help to level the playing field.

India has decided to supply 10 million doses of vaccine to Africa and one million to UN health workers under the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) facility of the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations (GAVI).

Among the individual countries, Bangladesh is the largest beneficiary, having received seven million doses of the Covishield vaccine, of which two million doses are in the form of a grant, while Nepal has received one million. Bhutan and Maldives have received 150,000 doses and 100,000 doses, respectively, while Sri Lanka and Afghanistan have received 500,000 doses each (Table 1).

Table 1: India’s COVID-19 Vaccine Supplies

| Country | Quantity Supplied (in ‘000 doses) | ||

| Grant | Commercial | Total | |

| Bangladesh | 2000 | 5000 | 7000 |

| Morocco | 0 | 6000 | 6000 |

| Myanmar | 1700 | 2000 | 3700 |

| Brazil | 0 | 2000 | 2000 |

| Nepal | 1000 | 0 | 1000 |

| South Africa | 0 | 1000 | 1000 |

| Sri Lanka | 500 | 0 | 500 |

| Afghanistan | 500 | 0 | 500 |

| Kuwait | 0 | 200 | 200 |

| UAE | 0 | 200 | 200 |

| Bhutan | 150 | 0 | 150 |

| Maldives | 100 | 0 | 100 |

| Mauritius | 100 | 0 | 100 |

| Bahrain | 100 | 0 | 100 |

| Oman | 100 | 0 | 100 |

| Barbados | 100 | 0 | 100 |

| Dominica | 70 | 0 | 70 |

| Seychelles | 50 | 0 | 50 |

| Egypt | 0 | 50 | 50 |

| Algeria | 0 | 50 | 50 |

| Total | 6470 | 16500 | 22970 |

Source: Ministry of External Affairs: Vaccine Supply, 2021.

Other than its South Asian neighbours, the Indian Government has supplied 1.5 million doses of the Covaxin vaccine to Myanmar. Mauritius and Seychelles have been sent 100,000 doses and 50,000 doses of Covishield, respectively. Several other countries, including Bahrain, Barbados, Dominica, Oman, are also part of India’s ‘vaccine assistance’ programme. Thus, India is using its soft power to assist developing countries, a role that it has increasingly been playing as a development partner.

Another important dimension of India as a supplier of COVID vaccines is that the government has allowed vaccine exports on a commercial basis to countries seeking them, while an embargo has been imposed on commercial sales of vaccines in India. Morocco, Brazil, and South Africa are among the countries that would benefit from this policy stance. Morocco is the largest importer of vaccines from India (6 million doses), while Brazil and South Africa have imported two and one million doses of Covishield, respectively.

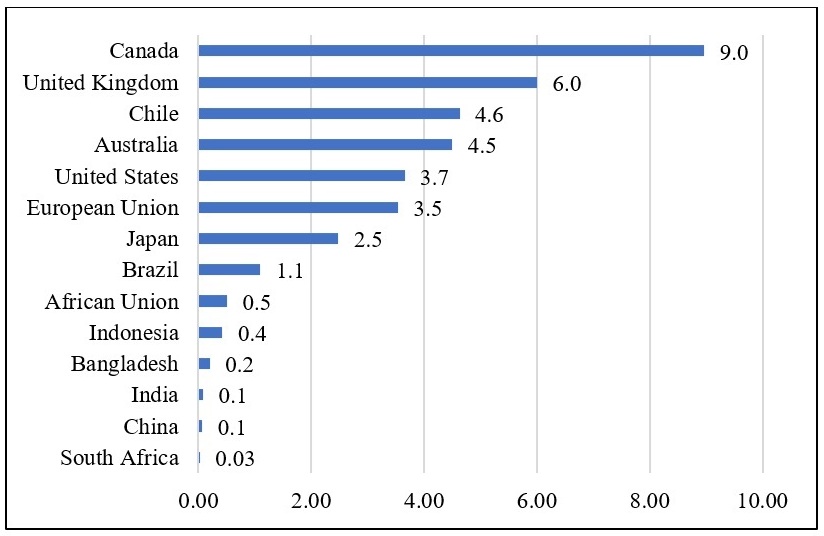

The government of India’s vaccine sharing policy with partner countries is undoubtedly a standout in times of the alarming precedent of ‘vaccine nationalism’ practiced by several countries. According to Duke University’s Global Health Institute, a group of advanced countries, accounting for only 16 percent of the world’s population, have secured for themselves 60 percent of the global vaccine supplies. Canada heads the list of ‘vaccine nationalists,’ having assured vaccine supplies nine times its population, while the United Kingdom has stocked enough doses to vaccinate every citizen six times. Other countries to secure vaccine supplies beyond their domestic requirements are Australia, Chile, the United States, and members of the European Union.

Figure 1: Availability of Vaccines Per Capita (as of February 8, 2021)

Source: The above data is compiled from three sources: (i) Total confirmed doses of vaccines procured by countries from Launch and Scale Speedometer, Duke Global Health Innovation Center; (ii) Population of individual countries for 2020 from Worldometer; (iii) EU population in 2020 from Eurostat.

Not surprisingly, global supplies have been seriously affected at a juncture when every country is trying to overcome the pandemic-induced crisis. Several studies have cautioned that inadequate availability of vaccines, especially for smaller countries, would prolong their recovery, thus triggering significant increases in global inequalities.

A Rand Corporation study has concluded that if low and low-middle income countries (LLMICs) are not able to adequately immunise their populations, high income countries (HICs) would be severely impacted. According to the study, the total cumulative economic cost for 30 HICs could increase from $82 billion in 2020–2021 to $258 billion in 2023–2024. The United States could incur the highest relative cost, $15.7 billion in 2020–2021, rising to $49.3 billion in 2023–2024, while the corresponding figures for Germany were estimated to be $9.9 billion and $31.1 billion, respectively.

A recent study commissioned by the International Chamber of Commerce has observed that equitable distribution of vaccines is in every country’s economic interest, especially those that mostly depend on trade. The study concludes that assuming that all HICs fully vaccinate their populations by the middle of 2021 and poorer countries find themselves largely excluded, the global economy could lose upward of $9 trillion, which is larger than the combined GDP of Japan and Germany.

In October 2020, India, along with South Africa, had taken an important initiative to ensure accessibility and affordability of COVID-related vaccines, medicines, and related products through their proposal in the World Trade Organization (WTO). The two countries, and nine other countries that have since supported them, argued in favour of granting a waiver from the members’ commitments to implement or apply four forms of intellectual property rights so that these critical products and their technologies are widely available.

India’s twin initiatives to make vaccines widely available to developing countries, together with the growing evidence of the benefits of making COVID vaccines accessible, could lead to the recognition that in pandemic times, medical products must be treated as global public goods.

Biswajit Dhar is a Professor of Economics at the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.

Image courtesy of S. Jaishankar